My Trip To San Jose

Something I’ve noticed throughout my journey in martial arts is that while the more militaristic Japanese style with belts and ranks seems to suit my specific learning style better, the familial “skill family” approach of the Chinese arts seems to produce students with a much deeper understanding of the theoretical side of their arts. That’s why while on vacation in San Jose, California this past week, I jumped at the opportunity to meet and learn from Sifu Ben Der, founder of San Jose Wing Chun, who turned 83 years old this week. As one of the preeminent scholars of Leung Sheung lineage Wing Chun, a lineage famous for their attention to detail, if anybody could help me reach greater insights into why martial arts work, it would be him. While just one week with Sifu Ben is obviously nowhere near enough to make any claim to a knowledge of Wing Chun Kung Fu, I still feel like I have come away with some newfound wisdom and new concepts to think about.

This post does not have much in the way of a defined structure, it is mostly just my thoughts about Wing Chun as I go through the week.

Where Does Wing Chun Live?

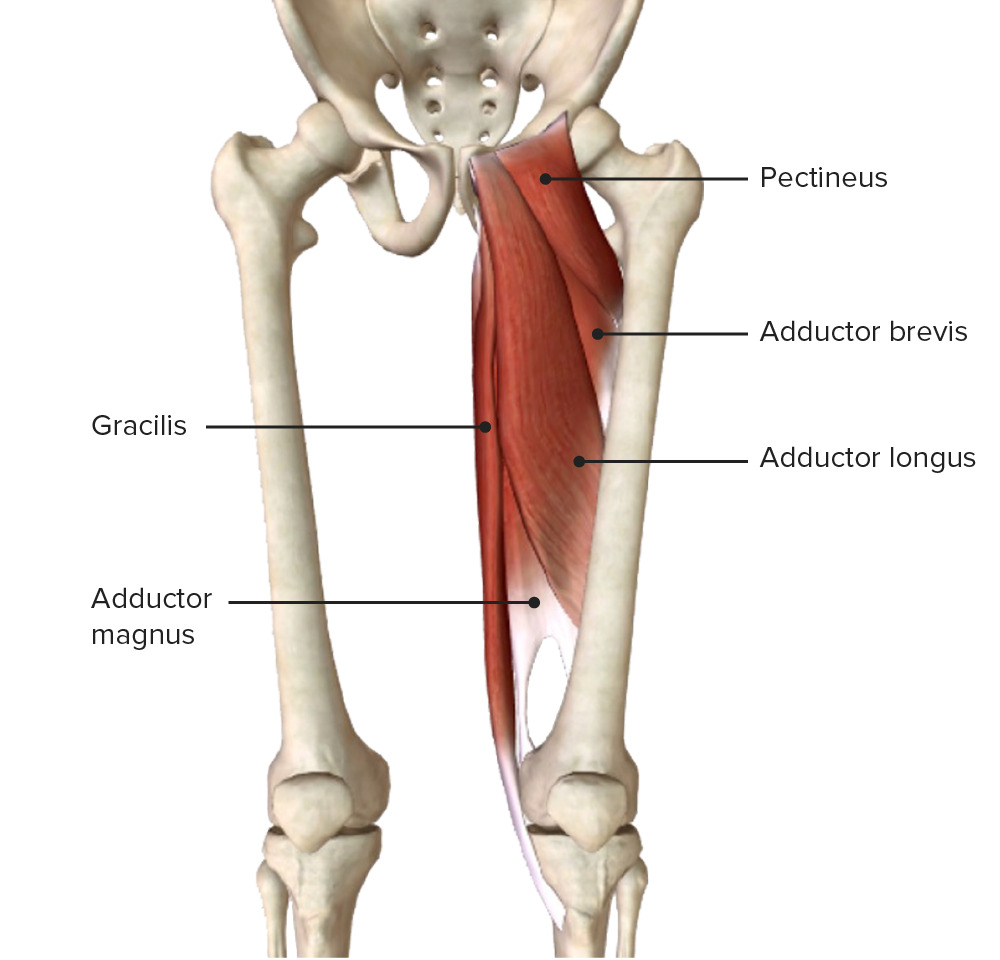

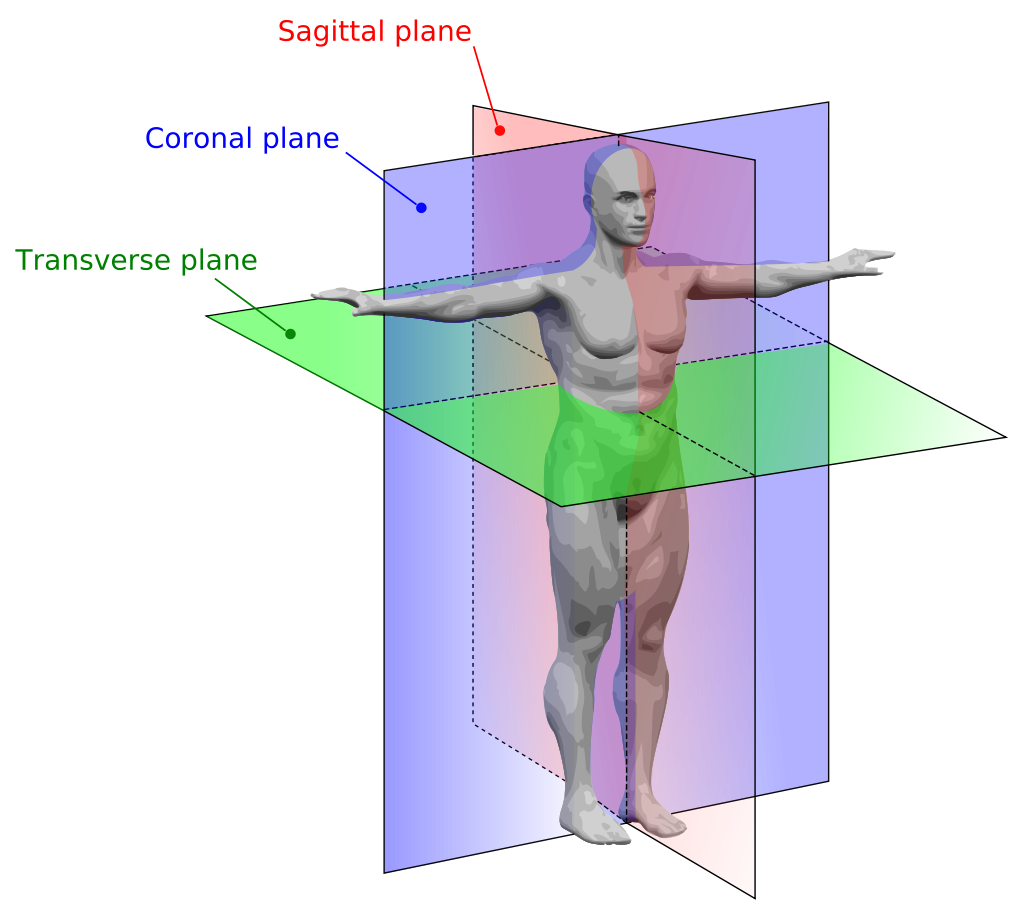

Wing Chun hands seem to live where the sagittal plane meets the diaphragm1. Everything else seems focused on reinforcing the sagittal plane. When settling into my horse, a consistent correction that I saw made of myself and others was where the hips are positioned. While it was uncomfortable to maintain that position at first, I noticed that my hips were being moved such that my center of mass was being positioned directly superior to the midpoint between my heels. With the center of mass correctly positioned above the midpoint between the heels, the horse uses tension of the adductor muscles2 to create counteracting levers preventing lateral motion to either side.

If the position of the opponent changes Wing Chun practitioners will pursue, rotating their sagittal plane to always keep the fight as medial as possible. High, lateral techniques like Fat Sau (拂手) do exist, but they are explicitly not ideal and designed to bring a lateral attack into the sagittal plane. As for the diaphragm, it seems to be where the hands are the strongest.

What Is Wing Chun Energy?

Sifu Ben regularly refers to putting “energy” into things. While at first I thought this referred to force, it quickly became apparently to me that there’s more to it than that. During Siu Nim Tao (小念頭), I was encouraged to have “forward energy” in my Wu Sau (護手) while bringing it backwards towards my sternum. With that energy I end up resisting my own motion to a minimal degree, but an opponent cannot collapse my elbow as easily by pressing from the front. This change did not fit with my understanding of energy simply meaning force. After conversations with Sifu Ben; Sifu Mark Leong of Honolulu Wing Chun; Rain of Fort Collins Wing Chun; and Sifu Steve Wong, one of Sifu Ben’s most senior students, I think I have come to a better understanding of what Sifu Ben means when he says “energy.” While this may seem like I am overanalyzing a very obvious and intuitive concept, it is my impression that Wing Chun has a very unique kind of energy and I believe this is its secret to better serving smaller, typically weaker people like Leung Yee Tai or Yim Wing Chun, the woman the art is named for.

Wing Chun is built around internal connection and viewing the body as one whole interconnected system. When you consider a jab in boxing, for example, there are other components but the fist and the tricep are the stars of the show, so to speak. Legendary boxers are described as having “arms like cannons,” effectively utilizing the full strength slow-twitch3 muscle fibers to maximize their impact with long windups. Wing Chun, on the other hand, is famous for its ability to deliver heavy hits without the same telegraphing windup in the one-inch punch. How? I have frequently heard the generic “energy comes from the ground,” but I was not satisfied with that answer. After having those conversations, I have concluded that, unlike the slow-twitch limb energy of boxers, Wing Chun energy is using your knees to leverage against the ground, translating and rotating the center of mass to use the full mass of the collective body to affect the periphery with more kinetic energy than the individual limb. In my opinion, this distinction is most visible in the Double Lan Sau (雙攔手) technique.

Timing and Disrupting the Resonant Frequency

Timing is a very important component of Wing Chun techniques. An example demonstrated by Sifu Ben was stepping into an opponent’s frame. If the opponent is well rooted, it is easier for them to keep you out. If they are stepping, they are most vulnerable to such an intrusion at the height of their step. A moving opponent forms a resonant frequency with the optimal timing for advancement at the peaks.